THE GARDEN

Traditionally, garden photography has been associated with depictions of scenic picturesque landscapes, charming garden vignettes, the recording of botanical or horticultural rarities. These often indulgent representations seek to recreate the nostalgic, dreamlike qualities of a mythical idyll- an earthly paradise. Even when more recently, edgier photographers have taken on the subject –they are beguiled by the beauty of the ‘natural’ and fall victim to the seductive powers of the flower, vegetable and fruit. Not that this is necessarily a bad thing.

-

Plants and gardens are inordinately seductive. Robert Mappelthorpe, for

example, explored the sensuality of the plant and achieved startling images that initially had the power to shock but they too soon became part of the ‘gardenesque’ vocabulary and aesthetic templates for the flower arranger.Since the late 19th century photographers from Eugène Atget to Edward Steichen have explored the garden’s mythological, erotic, political and scientific associations. These photographers also helped establish a tradition that ‘serious’ garden and landscape photography would be in black and white. Colour became associated with garden and horticultural illustration. A.E. Bye black and white images in Art into Landscape, Landscape into Art were studies in composition, texture, light and shadow that became iconic representations of the American landscape. Similarly, in the UK, the black and white work of Fay Godwin had enormous influence over the way we saw the British landscape. Interestingly, both their later work in colour was initially not seen as so aesthetically or politically effective. Today, however, this perception is changing and Roy Mehta, like many other young photographers, is reinventing the language of photography to show us new truths about nature.

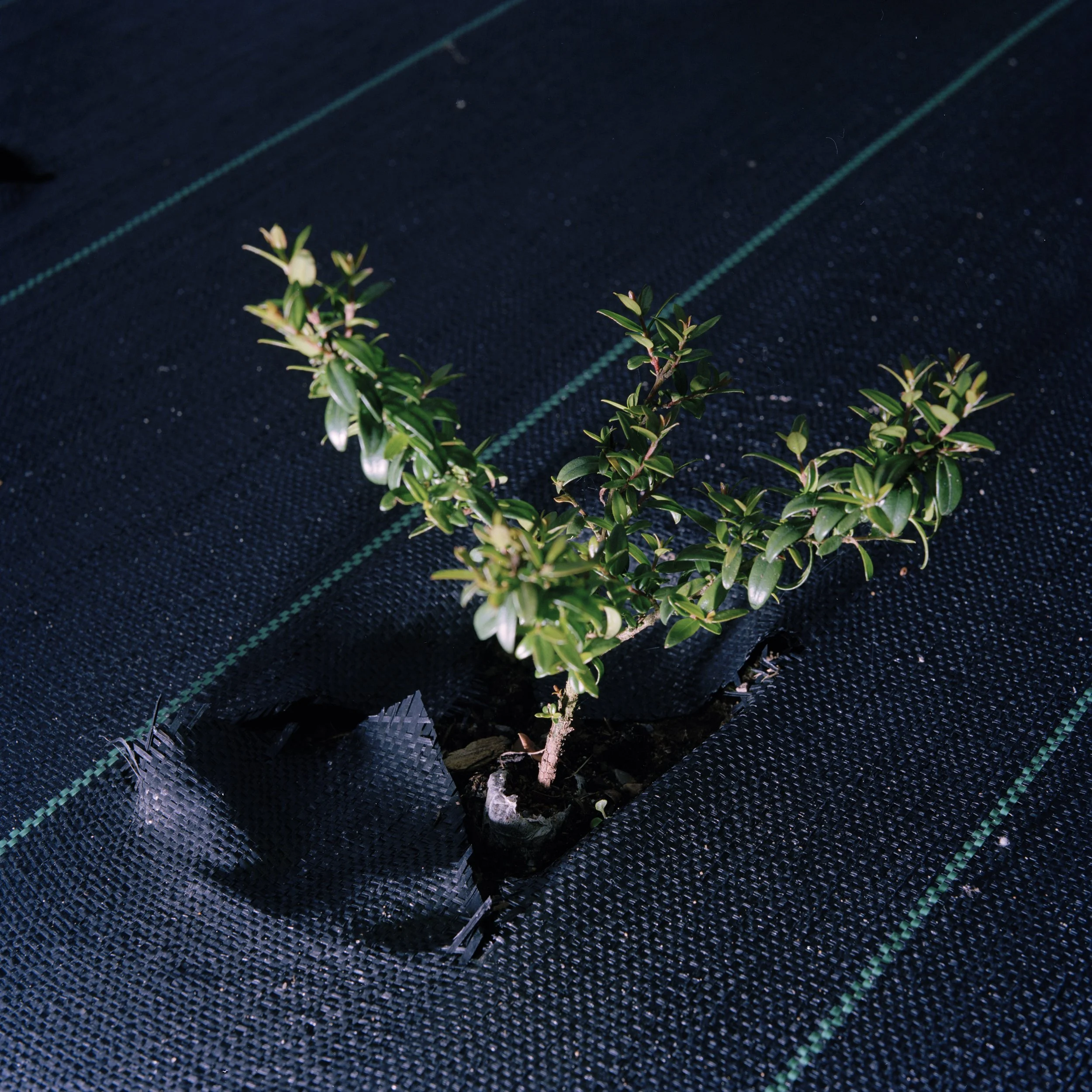

Form, line, texture and colour are the basic elements of visual composition whether in photography or gardening. The controlled precision which Mehta brings to his photographs echoes that worked by the horticulturalist on his subjects. Like the gardener, Mehta appreciates the anarchic forms of the untrained but also appreciates the order introduced into a composition by the bounded form.

‘Here the outside is arranged… portraying comforts and dangers enlarged or diminished …Trees, bushes… show us closeness, separation, dependence, arrest, depression, exultation...’ Robert Harbison Eccentric Spaces. In these images there is an estrangement between object, time and place. Though there are signs of growth and decay, the temporal aspects are suppressed-it is not clear whether we are witnessing the beginning or end of a cycle.The plants have undergone genetic and mechanical modification. They have become metaphors for adaption. They project that they were acted upon; that they resisted and submitted at the same time. Their soft tissue mimics the forms of metal. While there is evidence of their intervention, the gardeners are physically absent. But this is a record of their efforts to control the unpredictability of the organic world and this cannot be achieved passively. The methods and procedures of cultivation are aggressive. Nature is manipulated and transformed. The living organism is tamed or frozen into a formal code. The garden is a theatre of operations and is operatic in its theatricality. Surgical methods are used to cut, splice and graft tissue. Interventions are isolated, documented and recorded by the tightly focused lens. These photographs can be read as both metaphorical and morphological representations of our uneasy relationship with the natural.

©Greer Crawley, Buckinghamshire Chilterns University College 2011